“How has exhibition stand building changed over the years?” a blog by Lesley Russon

INTERNATIONAL CHAPTER

UK CHAPTER

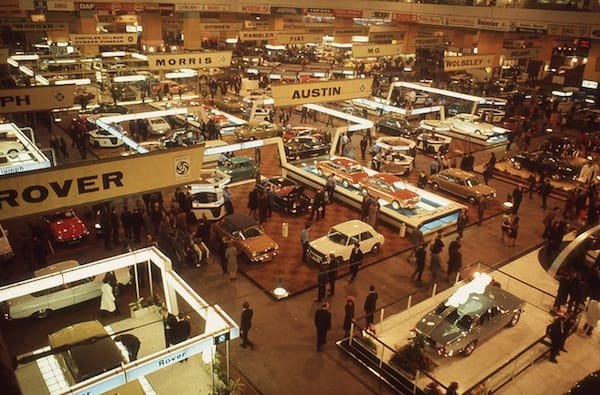

When the NEC opened in the 1970’s it represented a significant evolution in the UK exhibition industry.

Unlike Earls Court and Olympia, it was purpose-built and offered modern facilities and services, although the design and construction industry which served it was relatively unsophisticated, consisting of large contractors with little understanding of the exhibition world but a ready appreciation of the profits it offered, and smaller joinery specialists who recognised a golden opportunity to establish themselves and develop in a new arena.

Both, however, were stifled by the suffocating presence of the trades unions who saw the NEC as the perfect place to exert their influence. Everyone working on site, without exception, was a union member and carried a card defining what they could and couldn`t do, and stands could be closed down if the practitioner of one trade dared to offer a helping hand to a fellow worker engaged in some other trade. Union convenors became all-powerful, often aided and abetted by the big contractors who saw them as a means of keeping unregulated non-union firms out of the industry, thus helping to maintain their own pre-eminence in the industry.

Fortunately, this nightmare practice came to an end in the 80`s and the NEC blossomed.

The design world was also undergoing a revolution. Clients who had previously contented themselves with modest stands saw the NEC as a stage not only to promote themselves but also to outshine their competitors, and the challenge was there for designers to innovate and meet this new demand.

The industry became more sophisticated as designers and stand builders competed to win clients. Clients themselves were ever- more ambitious, stand designs and structures became bolder and more innovative, and stand builders were challenged to create structures which, a few years earlier, would have been unthinkable. The materials available were still relatively modest, as was the machinery employed to fashion them, so much depended on the talent and imagination of the workforce, and the skillful exhibition chippy became a highly prized individual.

Designs were becoming more radical, but were still drawn by hand and often took several days to produce, revisions to designs were equally painstaking, and the process was, inevitably, a slow one, involving considerable skill, as well as imagination, on the part of the designer.

Concept designs usually took the form of presentation on A1 boards, hand-drawn and rendered with felt-tipped pens or water colours, optional design colour changes were shown on overlapping plastic sheets that could be lifted to view an alternative choice. Presentations were delivered to the client in person by the contractor, or via the postal or parcel service, and if the submission was successful and won the contract, a working drawing would be produced with drafting pens on tracing paper, yet another slow procedure. Designers became skilled at the delicate task of amending working drawings by painstakingly scraping off ink from the surface of the tracing paper without tearing it, using an astonishingly sharp scalpel blade, rubbing over the area with an eraser to smooth the surface, and making the changes required, the alternative being to completely re-draw the whole thing.

The working drawing was then fed through a dyeline machine – a pungent, malodorous contraption filled with ammonia, which produced a blueprint, a copy of the original which could be folded and sent by post to clients, organisers, or contractor.

As a final luxury, the most valued clients might be presented with a model, a ravishing creation in card, garnished with glue and decorated with bits of foam dipped in green ink to represent plants. Woe betide the contractor who misjudged the size of a revolving door and became trapped with one of these fragile but cumbersome masterpieces.

Today computers have revolutionised the industry. Whilst the skills of the designer who could produce a vivid hand-drawn visual are enviable, computers have enabled designers who may lack the ability to draw, but who possess an abundance of imagination, to flourish. Visuals can be on the client’s desk top in seconds, changes are made in a matter of minutes, not days, and working drawings produced in cad can be sent to cnc machines capable of producing work of remarkable complexity and accuracy.

Has new technology had any impact on stand building?

3-d design programmes liberated the designer from the constraints of hand-drawn perspectives. Not only could visuals of unerring accuracy be achieved relatively quickly, but the use of new complex shapes was encouraged by the inherent capabilities of the programmes themselves. Whereas a hand-drawn visual provided a single point of view, computer generated structures can be viewed from 360 degrees, enabling the designer to be more thorough, and allowing the client a better appreciation of the geometry and flavour of the design. Lighting is more realistic, as are materials and finishes and graphics.

The existence of this technology, of course, is no guarantee of excellence, and the designer is not merely the operator of a contraption with its own inbuilt imagination. It simply allows the designer`s imagination scope for fuller expression, and provides a platform to explore new ideas.

The advent of Cad drawings and cnc machines transformed what can be built. Previously, contractors encouraged the use of stock stand-building materials. Some still do, but for those relishing a challenge, the technology is there to explore more challenging ideas. The subject of sustainable stand building is another discussion for another time.

Bringing us bang up to date, we are presently in a time in history on “how will the live event industry look like after Covid 19”. Technology in 2021 has definitely become top of the list, but face to face meetings will always be desired as a race we are sociable and need that interaction, seeing, feeling and living the moment of being together therefore live events will live on. Changes are always inevitable and virtual shows are now being developed, they have their place and the thought of the hybrid events could be here to stay and part of the new generation.

After all, once exhibitions stop being visually fascinating, their attraction will wane and we`ll be left with the aesthetic desert of the shell scheme, and where`s the appeal in that?

A blog by Lesley Russon, Managing Director ShowOff Display

Write a comment